- Home

- Mycelium Intro

- Fungi Origins

The ancient origins of fungi – How mycelium transformed life on earth.

Grab a coffee… this is a deep, deep dive into the origins and diversity of fungi on our planet.

The Fungi Kingdom is the largest group of living organisms that exist on our planet. It is also one of the oldest kingdoms, with origins stretching back more than one billion years.

Lacking fossilized evidence, fungi’s evolution was murky and mysterious. Neither fungal structures nor mycelium lend themselves to preservation – their very nature is to decompose. Only in the past fifty years have scientists begun to understand how fungi evolved on earth.

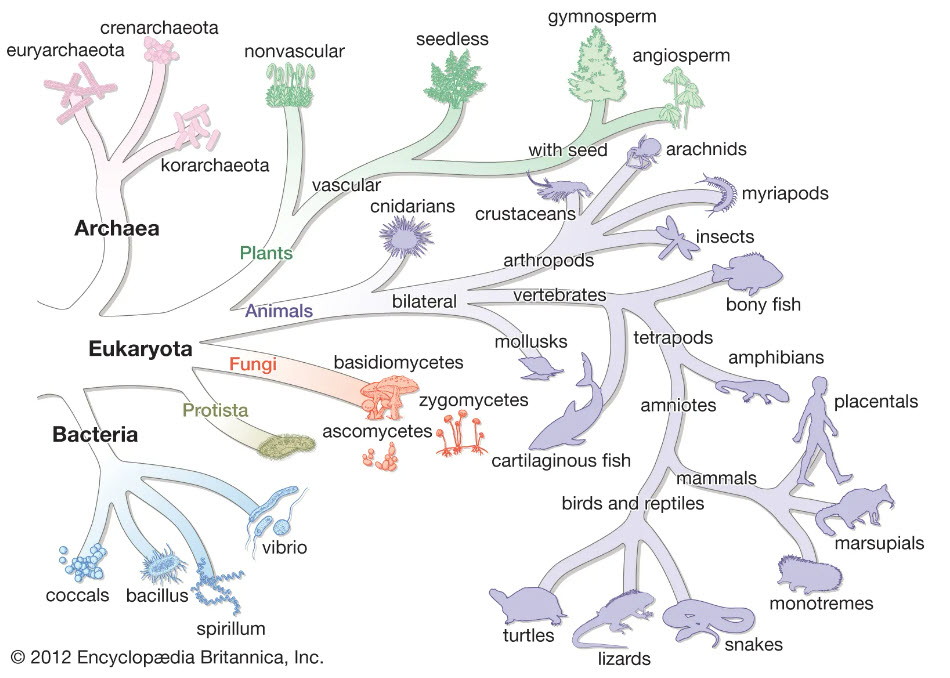

The history of mycology was revolutionized in the 1960’s thanks to electron microscopy and subcellular molecular analysis. These breakthroughs helped biologists identify three great domains to classify all living organisms on earth – Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. And shed light on fungi’s ancient origins.

Three domains of evolution.

Phylogenic domains (evolutionary relationships) are defined by shared characteristics of cell type, reproduction, and nutrient acquisition. The two most basic life forms are prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

Archaea and bacteria are prokaryotes – single-celled organisms without a defined nucleus. And the oldest life forms on our planet.

Fungi are eukaryotes: a group of organisms (including plants, animals, and protists) whose cells contain a defined nucleus and organelles inside a plasma membrane. Organelles can be mitochondrial (animal and fungal cells), or chloroplasts (plant cells).

Eukaryotes evolved from the earliest prokaryotes between 1.6 and 2.7 billion years ago.

Protists were the third life form on earth – amoebas, protozoa, diatoms, slime molds, and some algae. Once thought to be fungi, biologists now agree they are a biologically distinct kingdom.

Fungi were the fourth kingdom of life to evolve, as unicellular organisms in a primordial ocean teaming with super-colonies of archaea and bacteria.

Multicellular eukaryotes (plants, animals, and fungi) diverged as separate kingdoms 900 million years ago. While their cellular makeup is quite different, they all share common functions of locomotion, reproduction, respiration, digestion, and excretion.

Fungi - The fourth kingdom of life.

As a taxonomic group, fungi are monophyletic – meaning all modern fungi can be traced back to one single ancestor organism. In the absence of fossil evidence, researchers rely on biochemical markers to trace the shrouded origins of fungi.

Until the 1960’s, fungi were originally thought to be part of the Plant Kingdom. But in the past fifty years, mycologists have discovered that fungi are actually more closely related to animals – not plants.

Fungi diverged from an unknown animal ancestor between 800 to 900-million years ago.

The ancestor of Fungi was likely a unicellular marine organism that lost its filament tail as it transitioned onto land, and later evolved into multicellular mycelium colonies.

Molecular analysis developed in the 1990’s deepened our understanding of fungal evolution and established their familial relationship to animals. The genetic link between fungi and animals is chitin – a glucosamine polymer found in fungal cell walls and in invertebrate exoskeletons.

Animal sperm and some zoospores also share one posterior flagellum – a whip-like filament that extends from the ends of all simple life forms.

Fungi’s taxonomy is based on the composition of cellular walls, enzyme organization, and lysine synthesis (an amino acid). Classification is divided into 7 phyla, 10 subphyla, 35 classes, 12 subclasses, and 129 orders – including mycelium, mushrooms, lichens, eukaryotic algae, mosses, yeasts, molds, rusts, cankers, and smuts.

Scientists have identified over 144,000 fungi species, but mycologists believe there are 2-3 million fungi species on earth.

Chytridiomycota are one of seven Phyla that comprise the Fourth Kingdom, and believed to be modern descendants of the first fungal organism. Microscopic fungi (cryptomycota), are the only fungi whose walls do not contain chitin and still possess a flagellum. Ribosomal RNA analyses support that cryptomycota are the oldest known fungi species.

Slime molds and water molds (once considered fungi) were also reclassified in recent decades as protists – protozoan animals that predate fungal eukaryotes.

Adaptable diversity & breathtaking abundance.

Fungi are incredibly diverse and adaptable. Like bacteria, there is nowhere on earth that fungi don’t inhabit – and in staggering numbers. They populate every marine environment (salt water and fresh water), and thrive in brackish saline habitats and polluted waters where little else survives. Fungal species also live in polar regions of the Arctic and Antarctica.

Fungi inhabit the air we breathe, soils, and in our food. Fungi live on plants, animals, textiles, and inside our bodies. We use yeasts to make bread, beer, wine, and cheese, and enjoy fungal fruits like mushrooms and truffles.

Fungi obtain nutrition through decomposition, or as biotrophs (parasites), excreting enzymes to break down and absorb external nutrients. They possess antiviral, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory traits that fight cancer and disease. And play a crucial role in the carbon cycle of our planet.

Fungi not only survived several mass-extinction events, but helped other plants and mammals survive cataclysmic environmental changes. Without fungi, biodiversity on earth would collapse.

Terrestrial trailblazers.

Fungi were one of the first multicellular organisms to inhabit the barren continents. They obtained mineral nourishment from rocks and helped create soils, providing essential nutrients for terrestrial species. Mycelium established symbiotic relationships with other prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Fungi’s diversity of form and function ushered in major phenotypic changes that may have helped fungi leave the intertidal zones. Key adaptations were hyphae development, cellular wall changes, sexual structure innovations, and mating signals. But what drove these genetic variations remains unknown.

Devonian landscape depiction with Prototaxites by Artist Mary Parrish, 2000 – Photo by Smithsonian Institution

Devonian landscape depiction with Prototaxites by Artist Mary Parrish, 2000 – Photo by Smithsonian InstitutionOne of the largest fungi known evolved 460 million years ago. Long before trees existed, enormous mega-fungi called prototaxites towered over the prehistoric landscape, growing as tall as 8m, and 1m wide.

These giant fungi dominated global ecosystems for over 40 million years, when land was populated with small invertebrates and early plants. Prototaxites are one of the few fungi fossils discovered. Their dense fibrous bodies preserved in stone provide evidence of what they consumed with complex mycelium structures – feasting on cyanobacteria, algae, protists, lichen, mosses, and liverworts.

Prototaxites suddenly went extinct around 400 million years ago, after insects evolved and devoured them as a food source. Now industrial activities and synthetic toxins threaten fungi, insects, and organisms in every kingdom.

A subterranean empire.

Today, fungi operate mostly underground, out of sight. Mushrooms, molds, and lichen are the only visible evidence of fungi’s teaming global empire. Mycelium networks work silently in our soils and ecosystems as vast subterranean communities, communicating with other species via electrical pulses that make the earth hum.

With over one billion years of planetary experience, fungi have learned invaluable lessons that humans have yet to grasp – being small is an evolutionary advantage and interspecies collaboration is fundamental to survival.

Biological research continues to uncover and explore the ecological capabilities of these ancient organisms in bioremediation, medicine, and horticulture. But we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of fungi’s regenerative superpowers.

Related Topics:

Fungi have sex in a variety of interesting and surprising ways.

Their range of reproductive options gives fungi a unique survival advantage. Who knew? Read the full article...

How fungi communicate with language based on electrical impulses.

Researchers have uncovered how fungi communicate in a language based on electrical impulses. Read the full article...

4 Ways mushroom mycelium challenges our definitions of intelligence.

As humans we like to believe only our species is intelligent. Research into fungal mycelium is now challenging that assumption. Read the full article...

Mycelium… the underground network that connects and supports all life.

Mycelium is the miracle beneath our feet. It’s the root system of the mushrooms we see above ground, and a whole lot more. Read the full article...

Mycoremediation can help clean up large areas of polluted land and waters.

Mycoremediation is the use of fungal mycelium to help clean up oil spills, toxic soil at old industrial sites, and polluted waterways. Read the full article...